Exhibiting Un/Natural Histories

February 2023

This exhibition was integrated into an undergraduate course on natural history museums.

How do human ideas about society, power, and reproduction influence the collection and display of the natural world?

Natural history exhibitions often obscure how people have ordered nature through naming, categorizing, and display. Naturalists and early scientists often captured specimens of flora and fauna on colonial expeditions, prioritizing spectacular and “exotic” specimens over less showy species, and frequently naming their finds after European explorers, Western rulers or polities, and Roman mythological figures. They also named invasive species after immigrant groups or with ethnic slurs.

Natural history displays also bear traces of human cultural constructs about gender and sex: for example, many animal dioramas depict heterosexual, monogamous couplings, despite more varied reproductive practices in nature. Displays frequently encode patriarchal norms against a more complex reality. In these ways, natural history specimens can reveal the cultural milieu of the time of their collection, and the personal priorities, worldviews, and ambitions of their collectors.

Using specimens from the CoW Biology Dept Collections and Herbarium, we highlight some of the ways human cultural beliefs and practices shape natural history museum displays. What is natural in natural history museums? Is it possible to erase human bias from the ways we re/present the natural world in museums?

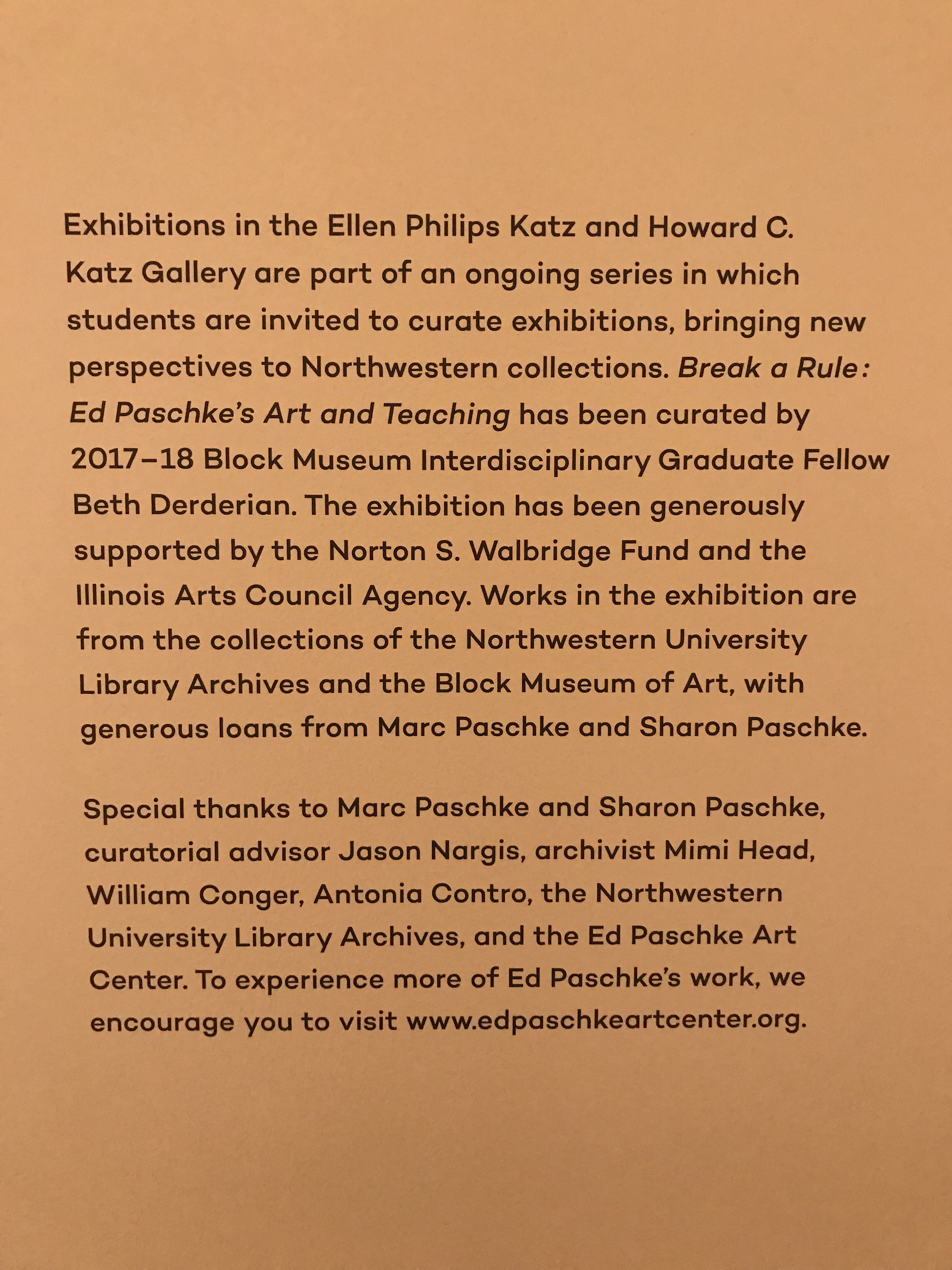

Break a Rule: Ed Paschke’s Art & Teaching

September 2018

I curated this exhibition as a Curatorial Fellow (2017-2018) at the Block Museum at Northwestern University.

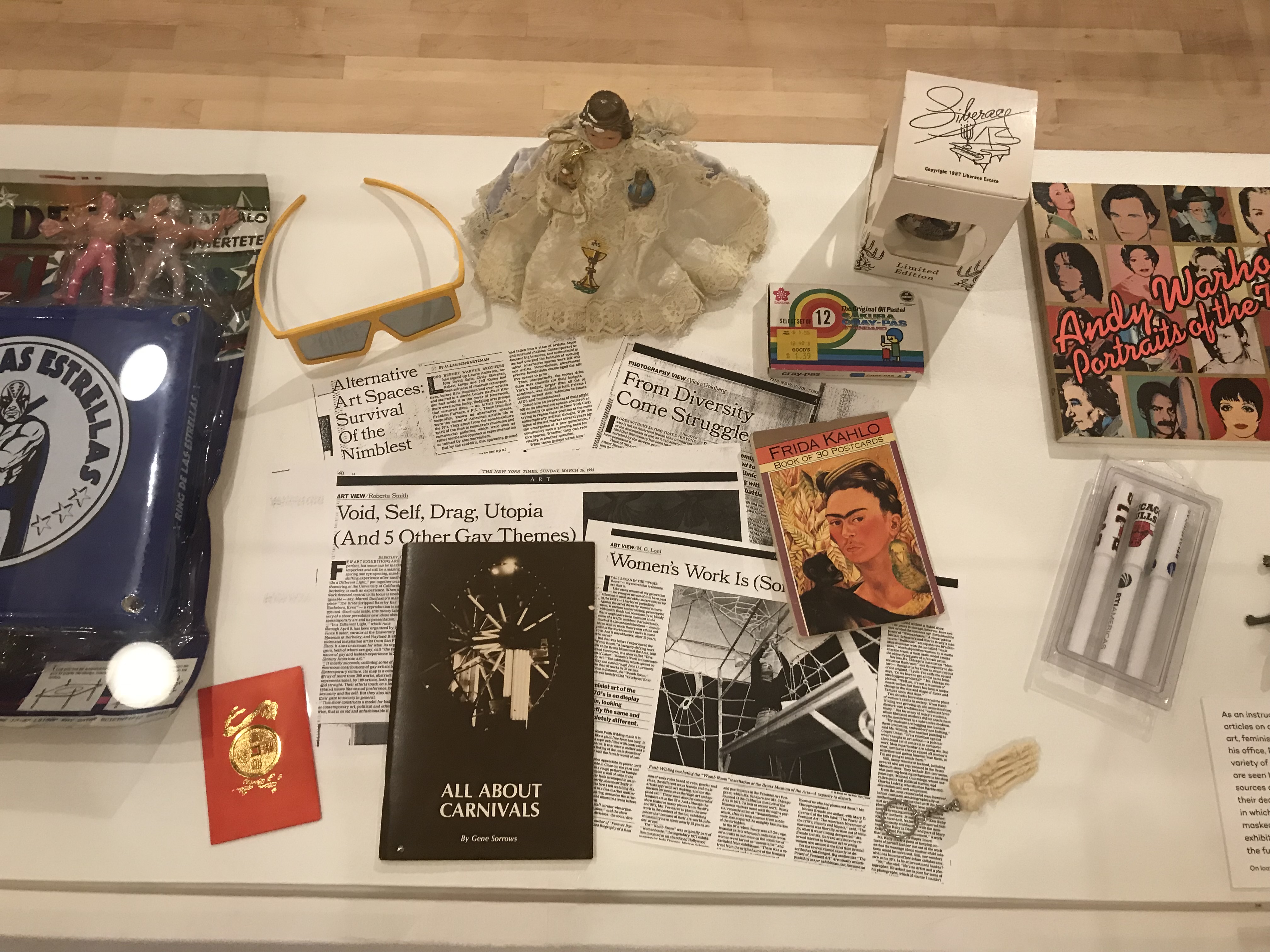

Ed Paschke (1939–2004) often began his classes with the assignment to “break a rule.” A bold innovator who enjoyed disrupting conventions, Paschke mentored students at over two and a half decades at Northwestern University to think outside the box. His work and his teaching were devoted to experimentation, playful exploration of the human experience, and capturing “every manner of humanity.” This exhibition considers his teaching alongside his art, foregrounding his printmaking along with self-produced pedagogical materials, to offer a new perspective on this well-known Chicago artist.

Paschke, who exhibited with the Chicago Imagists and gained recognition in the 1960s and 70s, is known for a range of subjects and characters often considered to be from the social margins. His own works also featured members of the many of Chicago’s various alternative communities, including strippers, burlesque dancers, Lucha Libre wrestlers, and boxers. However, he also sometimes took classic images, like a photograph of the head of the Sphinx, and experimented with color additions, adding symbols and patterns, and covered the original image to render it his own. The process of forging new ground required trusting one’s instincts, and Paschke noted that one challenge of teaching was encouraging intelligent students, accustomed to relying on logic, to break rules and trust their gut instinct. He also encouraged his students to get out of their comfort zone. This diversity and interaction he encouraged was in his words “the very pulse of life” and his attempt to capture it was central to his work. He often said that people loved his work or hated it, and either reaction was fine with him—as long as they were not indifferent.

The exhibit is organized around three tenets at the core of Ed Paschke’s teaching and artistic practices: learn the rules in order to break them, trust your instincts, and get out of your comfort zone. While Paschke taught his students basic techniques in painting and drawing, he also encouraged them to break rules and create something entirely their own.